Knowledge Strategy, Organization and Management, Security and Privacy

Building Positive Digital Futures

My weird dream

Lately I’ve been having weird dreams about the slow but insistent erosion of institutions, authorities, and knowledge — ‘a slow, slippery slide toward slop and sloven.’ One recent dream unfolds around the year 2073 — after the abolishment of the Food and Drug Administration. I’m having some pain on my left side, so I tele-visit my doctor. She says, “It could be this ailment, or it could be that one. I have a cabinet full of pills, I suggest you try one.” “What do you mean — which one?” “They all come highly recommended from their manufacturers — whom I know to all be well-intentioned people.” “Well, do they work? Has anyone else tried them?” “Great questions, wish I knew. Under the Science Off Our Backs (SOOB) Act of 2055, we’re not permitted to keep track of that kind of thing anymore.”

What is my dream telling me? What if this FDA-free future came to pass? We’d rightly be wary of trying a remedy for which there was no rigorous data as to its safety or efficacy. We’d rightly be equally wary of ingesting something whose ingredients and provenance we did not know. During the 20th century, we got used to not having to worry about these physical-world concerns. We could assume that food and drugs had been tested and found to be safe and effective (in the case of drugs) or nutritious (in the case of foods.)

No epistemic safeguards

Fast-backward to today. All of us enjoy many safeguards in our physical world — often to the point of taking them for granted. But no such guardrails exist at the societal level in our epistemic world. Information rushes at us continually — and makes up a huge portion of our mental ‘diet.’ But there’s no FDA for information — no labels for ingredients or warnings — no tests for safety or efficacy. We cannot assume — just because they’re offered on the market — that information and information-based products are safe, good for us, reliable, or effective on any level. On the contrary, it’s safer to assume that we are essentially being used as lab rats for information products whose effects are untested — and that such ’tests’ are not by nature controlled scientific experiments, but rather revenue-generating market transactions.

Technology and strategy

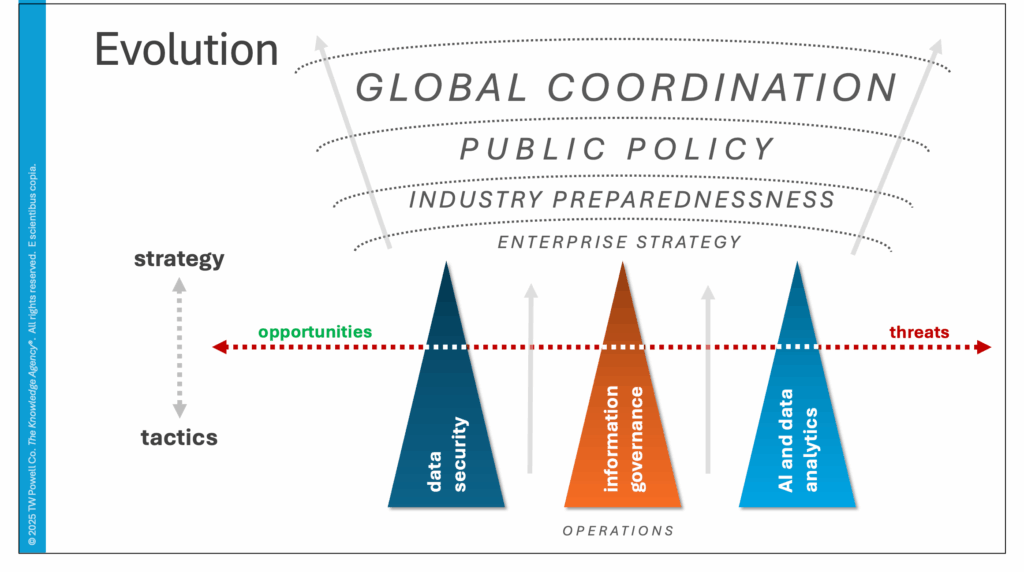

About a decade ago, when I was lecturing at Columbia, I showed this slide — trying to impress upon my knowledge strategy students how consequential their future jobs were destined to become.

My own career had begun long before that, in a time when there was virtually no digital technology in the workplace — then continued through several decades when digital was present in some form, but was largely operational/tactical/transactional. Approaching the turn of the century — with the Y2K near-disaster and the dot-com boom-crash — digital technologies were starting to make headlines and proliferate in the workplace (with their ubiquitous roles in our personal lives not far behind.)

But tech remained largely an IT-centric issue, with upper management primarily concerned that ‘the enterprise lights were being kept on.’ I remember becoming excited when Harvard professor Michael Porter declared in 1985 that, ‘Information gives you competitive advantage.’ It’s hard to recall that distant time when this idea — now assumed as table stakes — represented visionary thinking. On that simple insight, I built my career.

The frontier

We’ve now crossed that frontier into that future where digital is an essential element of competitive strategy — and, increasingly, its very core. Competing in the knowledge economy, as I’ve titled these posts for years, is now a daily reality for most organizations. It’s no longer a reach to say that Business Strategy = Digital Strategy.

But, according to research by The Conference Board and reinforced by my professional experience, organizational structures and capabilities have not fully caught up to that reality. Often the senior leaders of powerful organizations have little more than superficial understandings of technology — its capabilities, limitations, and ramifications. They’re sailing uncharted waters, aided by neither maps nor navigational instruments. Nor do they benefit from stories of those who have returned — since we’ve never been here before.

To shape and drive their technology agendas, they therefore depend on the supply side — tech vendors and third-parties like consultants — most of whom have financial interests in the outcomes. Such agendas too often wind up being less about ‘solving problems that we have now,’ and more about ‘how can we use this new technology that’s in the headlines, and that everyone else seems to be adopting?’ And, as they say, when you’re wielding a hammer, pretty much everything looks like a nail.

Naturally, such agendas ‘accentuate the positive’ — value is defined in terms of benefits, without corresponding weighing of tradeoffs — costs, uncertainties, and risks. Due diligence too often falls by the wayside, and Fear Of Missing Out takes the reins as a driving force.

Latest and greatest

Digital technologies, with their origins in the 1960s, have seen a relentless and accelerating pace of development since then. Generative AI is only the latest in a series of emerging technologies that organizations are urged to consider. Before that there was the metaverse, before that crypto and NFTs, before that the Internet of Things and self-driving cars — and some companies have yet to get a firm grip on social media. There will surely soon arrive something newer, even shinier and more promising. As adept as Silicon Valley is at inventing new technologies, they are arguably even better at creating aspirational hopes and dreams.

Given the lack of independent assurances mentioned above, each organization needs to conduct its own evaluations of new technologies. But rather than address each of these tech waves on a one-off basis, organizations could jump ahead of the curve by building a standing capability for evaluating and deploying emerging technologies on a regular, rolling basis. What would such a capability look like?

The TAG framework

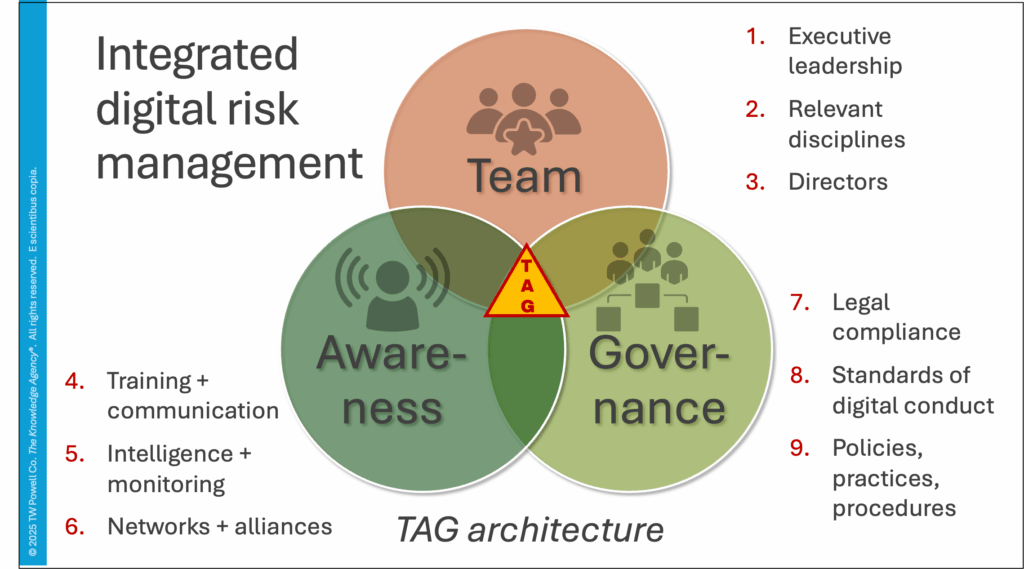

At its simplest level, an integrated digital risk management capability would integrate three fundamental elements: the Team, an Awareness program, and a Governance posture. Each of these elements would in turn consist of three sub-elements:

- The Team would consist of: (1) executive leadership direct involvement, with a designated CxO leader; (2) relevant other disciplines, for example human resources, communications, and end users; (3) directors (at least one).

- Awareness — (4) training of users; (5) continual intelligence regarding current developments; (6) networks, for example with academics and consultants working in this space.

- Governance — (7) legal compliance is a minimum; (8) standards of digital conduct that may go beyond compliance; (9) practices and procedures in sufficient detail to be communicated, understood, implemented, and enforced.

While most organizations have elements of this, we recommend the integrated approach described.

Digital technologies offer us great promise for productivity and innovation. These technologies are powerful — and, as such, carry risks and unintended consequences often hidden or ignored. In the absence of consistent regulation (in the US), creating enterprise guidelines and practices along these lines will help ensure sound digital practices — and may prevent or mitigate the next cyber-disaster. I’ve prepared a full presentation on this, please let me know if you’d like to discuss.

Comments RSS Feed