PARALLEL WORLDS 4: The Narrative Unbound

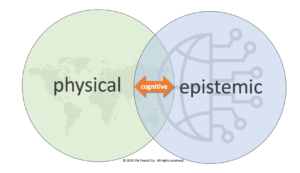

In drawing the Physical-Epistemic distinction. I’ve only hinted at a pivotal third aspect — the Cognitive World of human consciousness and knowledge. This forms the essential connective tissue between the two worlds.

Human knowledge has two root sources: the P and the E. We can directly observe ‘what is’ — “lived experience,” some call it — or we can gain our knowledge through Epistemic lenses — the prevailing narrative(s) about what is. The latter is how most of us acquire most of our knowledge — through consuming information: reading, hearing people talk, seeing videos, and so on. This ‘superpower’ extends our cognitive perimeters far beyond what any of us could experience directly.

Epistemic lenses miraculously allow us to see reality as represented in data, information, knowledge, and intelligence. They transform the vast, unfathomable nature of the Physical world into inputs for our cognitive models. We navigate partly by sensing the world in front of us — and partly through mental maps that contain aspects of reality, refined to a cognitively-manageable load.

Self-sustaining narratives

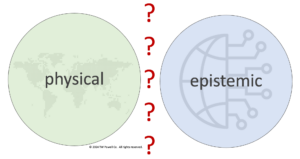

But — as with all things — there’s a trade-off. Even as they enable our perceptions, epistemic lenses also introduce their own narrative distortions — biases and editorial filters. And left unchecked, the E narrative can drift away, untethered from the underlying P reality. The epistemic world — the narrative — can eventually reach a point of being self-generating, self-sustaining, and self-fulfilling — where it no longer has reference points in the physical world to check or guide it.

Let’s assume that, when we act or believe, we prefer it to be on the basis of what is true. But how do we determine what is true — versus what is a narrative that has drifted from its underlying reality? How do we prevent the breaking of the primal P-E bond?

Fact-checking reality

In some ideal realm (that admittedly does not exist), we fact-check those things for which we do not already have direct experience before acting on them. Most of the time, however, this is not even remotely feasible. What happens instead is that we find reference points in the Epistemic world — trusted authorities to guide our actions, in lieu of direct Physical knowledge. These authorities — whether experts or friends we trust — form a powerful validation buffer.

Do we trust them because they’re authoritative — or find them authoritative because we trust them? Research (for example, this excellent piece from Google) shows that, in most cases, it’s more the latter at work. In practice, trust comes more often from social cues from our peers than from empirical fact-gathering. And, contrary to what you might assume, this has been found to be even more true for the highly intelligent than for the average person.

The rise of monoculture

Our culture and lives are increasingly media-driven; this once acted as a glue that held us together, epistemically speaking. Electronic broadcast media (radio, soon followed by television) were introduced around a century ago. They were, by nature, one-to-many. Their success soon created a concentration of media power, in the form of broadcast networks with footprints in many local markets.

One effect of this economic concentration was to create epistemic concentration. During much of the latter half of the 20th century, we in the US had access to only three TV networks. They all reported on (more or less) the same stories with (more or less) similar editorial lenses. We had a shared narrative, a monoculture — a sort of electronic town green.

The loss of monoculture

The monoculture began to erode with the rise of cable TV during the 1980s. This accelerated during the early 21st century, when we had a massive democratization of media — as ever-increasing numbers of us hold in our hands a smart phone that serves as de facto printing press, radio station, TV station, and so on. The economic and epistemic power that had been established by broadcast media began to fragment and migrate toward the internet and social media. We now have many-to-many electronic communications — shared globally by more than half the people on earth — a sudden quantum leap in our capabilities.

As a consequence, we no longer share a common narrative — but rather inhabit an epistemic mosaic of competing (and often non-compatible) micro-narratives. We see different sets of news, often don’t agree on frames of reference, and sometimes can’t even agree on basic facts. Our common authority reference points — science, the press, and expertise in general — seem perpetually under question, or even attack, their persuasive power and authority diminished.

The loss of meaning

This is dangerous for any society; if we can’t fix this, the consequences could be disastrous. Aldous Huxley, author of the dystopian Brave New World, offered this warning about a media-besotted culture: “A society — most of whose members spend a great part of their time, not on the spot, not here and now and in the calculable future, but somewhere else, in the irrelevant others worlds of sport and soap opera, of mythology and metaphysical fantasy — will find it hard to resist the encroachments of those who would manipulate and control it.” Sound familiar? He was writing in 1958 about the use of propaganda in totalitarian regimes.

Untethered, ungrounded narratives are breedings grounds for economic bubbles, social manias, groupthink, cults, illusions, delusions, conspiracy theories, and other forms of MDM information (mis-, dis-, and mal-.) As Mark Twain said, “It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.”

Piercing the narrative veil

One solution for any self-sustaining narrative is simply to force some kind of reconciliation or grounding between the E world narrative with the P world — in this case, to fact-check life.

But not only is this impractical, as mentioned — recent research shows that it’s ineffective in aligning the P and E. Counterfactual narratives come equipped with their own reality buffers, reinforced by social cues and tribal acceptance. If ‘my peeps’ say this is how it is, it’s how it is.

Plato’s metaphor of the cave describes this narrative veil behind which each of us lives. The last scene is especially instructive; when the cave dwellers are finally brought to the surface to see real life, they are blinded by the light — and do not believe that what they are seeing is real. They long to return to their comfortable shared narrative in the cave — whether ‘real’ or not.

Having my spent my career in search of ‘good’ information for my clients, this series has been my attempt to grapple with the persistent power and influence of ‘bad’ information — even in our hyper-wired world. I had promised to give things a rest here — but I can’t in good conscience leave you on such a dark note. So next time I’ll wrap the series by proposing some ways we might actively address P-E drift.

Comments RSS Feed