War of the Words

That title’s not a typo — it’s an homage to the 19th century inventor of a wildly successful new form of story — science fiction. H.G. Wells authored many stories and non-fiction books, but is best-remembered now for his mind-bending tales The Time Machine, The Invisible Man, and War of the Worlds.

Wells attributed his success to one simple formula, which he used in his most successful work: wrap one fantastic premise in an otherwise truthful, believable narrative. He had arrived at one simple truth about human cognition, which I’ll call the Wells Effect: An untruth is most appealing — and most seemingly credible — when camouflaged in a sheath of accepted truths. Get ‘em nodding yes, the reasoning goes, and they’ll believe most anything. To be continued…

My hilarious — and terrifying — hour with ChatGPT

It took me weeks to get around to testing ChatGPT — during which time I had absorbed (and contributed to) the frenzied dialogue about how it was either a game changer that would revolutionize knowledge work and our entire economy, or a cataclysmic threat that would bring down democracy, Western civilization, and even human life itself. Either way, my expectations had been set that “Chat” (we’re friends now) was something momentous, to be reckoned with attentively and seriously.

When I finally used Chat, my immediate reaction was, Is that all there is? It seemed amusing enough, producing shop-worn “insights” in uninspired, bland language. But, to be fair, it did so in a way that I, along with others, got the feeling we were talking to a real person — even a super-intelligent one — who was fair, non-judgmental, and (probably most important) paying rapt attention to every little thing we said. Who would not find that appealing?

And Chat did not say anything offensive, flirtatious, or otherwise out-of-bounds — nor did I push it (him? her?) to do so. Most of what it said was “true-ish” — you might think it was true, if you didn’t know better.

I admit I was put off by Chat’s frequent disclaimers to the effect, I don’t know that, I’m just a machine. Firstly, it doesn’t know anything in any conventional sense of the word “know.” Secondly, it’s conveniently neglecting to mention that a human (or team of humans) programmed it to say that.

What’s truth got to do with it?

We are told by the purveyors and promotors of this technology that we should never use its results without first fact-checking them. Given that there are no sources or citations referenced, this sounds like more work than just doing the research in the first place. So I decided to test it by using a subject I know well — and which is available in several versions on the internet, most of them crafted directly or indirectly by me — my own professional life. I used my full name, which Google has no trouble identifying as the one and only me, to find my biography.

I’m aware that under the hood of Chat and other LLMs lie statistical models of how frequently words occur near each other in some test database — in this case, unspecified scrapings from unspecified parts of the internet. So its outputs are stochastic, not deterministic — meaning that I might receive different results on successive iterations. I tested this by running the identical query a dozen times in quick succession. The results varied significantly. In only one of these runs (the ninth one, curiously) did Chat admit it had no idea who I am. Each of the other times, it was in the ballpark — not unlike how a fiction writer’s account of me might read. But in seeking anything completely true, I might as well have been looking for a diamond ring in a landfill.

In its dozen renderings of my professional life, Chat credited me with founding and/or leading 20 different companies and writing 13 books. In fact, I founded one company and wrote four published books. To its credit, it mentioned the The Knowledge Agency five times, versus a single mention of each of the other 19 companies. On books, it got one correct out of the 13 mentioned.

What was more interesting is that, while all 19 of the “wrong” companies actually exist, only 5 of the 13 books exist as specified by Chat — the rest were hallucinations.

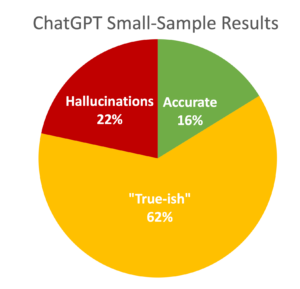

Here’s how the 37 combined company/book mentions broke down in my small-sample test:

Here’s how the 37 combined company/book mentions broke down in my small-sample test:

- 16% accurate — with repeated correct company mentions weighted appropriately

- 22% hallucinations — books titles that do not exist on Amazon

- 62% “true-ish” — books that exist, but in which I played no role

Though the hallucinations are unsettling enough, it’s the “true-ish” that most concern me — in that they contain just enough truth to seem credible from a distance. I am reminded of the Wells Effect described above.

Granted, this was small sample, and granted, these tools are getting more reliable with successive versions — but is the approach itself valid — or just click-worthy good fun?

The light fantastic

Rather than focusing on what ChatGPT is not — a truth and logic machine — let’s take it for what it is — an indefatigable robotic fantast in much the same spirit as H.G. Wells. If you want a summary of what “many people were saying” when the model was trained, delivered in anodyne, flavorless writing — whether prose, poetry, or code — LLMs are for you.

Call me a snobby connoisseur of truth, but my quality standards — and those of my clients — are too high for this to be useful to me. My clients expect pharmaceuticals-grade information — clearly sourced, vetted, and cross-checked — and hedged, where appropriate. Not surprisingly, my firm developed a technique for large pharma companies to, of all things, detect the availability on the internet of counterfeits of their products.

Chat reminds me of that — counterfeit knowledge. It looks real enough from a distance — but that’s skin-deep at best — and you have to be willing to suspend some disbelief. Remember the knockoff Rolex watches that you used to be able to buy on Canal Street here in New York City for $50? Impressive to your friends — until they get the idea that you’re either a pretentious dupe (if you took it seriously), or someone who doesn’t recognize or care about quality (if you didn’t).

Knock-off watches don’t hurt people. But the counterfeit prescription drugs we were engaged to hunt do — through a toxic mix of lack of effectiveness, harmful ingredients, and erosion of trust in the producer’s brand. The effects of counterfeit knowledge remain to be studied — but I cannot believe they are positive. We should take what we put into our minds just as seriously as what we put into our bodies.

War of the Worlds

When commercial radio was still fairly new in 1938, the young Orson Welles famously staged a live radio play of War of the Worlds. Welles stayed true to the Wells Effect formula of making it all very realistic — except for the core premise that New Jersey was being invaded by malevolent Martians like those pictured above. In spite of repeated warnings that this was staged drama, the life-like “we interrupt this broadcast to give you the latest” flavor was successful in convincing hundreds of people to scramble into their cars to try to escape their impending doom.

It’s a core element of human nature to want to believe the fantastic, fallacious narrative — and to suspend (at least for a time) critical judgement when faced with something excitingly new. (Thinking of you, investors in Theranos, FTX, and so many others.) This is a human “feature” when used for fun, as H.G. Wells did — but can metastasize into a “bug” when taken seriously. We must be tirelessly vigilant against conflating fact with fantasy too often — lest the mental muscles we are born with to discern the differences eventually weaken and atrophy.

The dangers of generative transformers are not in the technology itself — but in our willingness to trust them without prior, rigorous due diligence. We can begin by requiring transparency into (1) how these tools work and (2) the quality and provenance of the data sets that were used to train them. UPDATE: I’ll be speaking on this at KMWorld in DC, Thursday, November 9 at 3:00pm. Hope to see you there!

“Chat credited me with founding and/or leading 20 different companies and writing 13 books. In fact, I founded one company and wrote four published books” Love this piece, which saves me trying ChatGPT right now as I get to benefit from your entertaining experience, Tim

Glad to oblige TJ — and thanks for your note — but I do encourage to try it for yourself at some point. Maybe this will help calibrate your expectations lower than mine were.